Paul Darke

A disabled writer and artist., Digital Disability

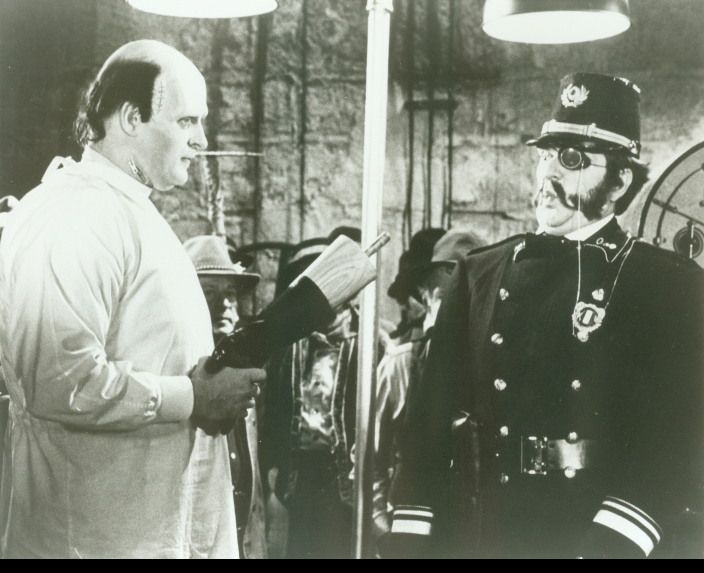

My favourite disability films are Mel Brooks' Young Frankenstein and Lars von Trier's The Idiots, because they both work with the knowledge that disability is intrinsic to the social and cultural illusions that perpetuate the fantasy that the 'normal' exists.

Alcoholism, AIDS and Disability